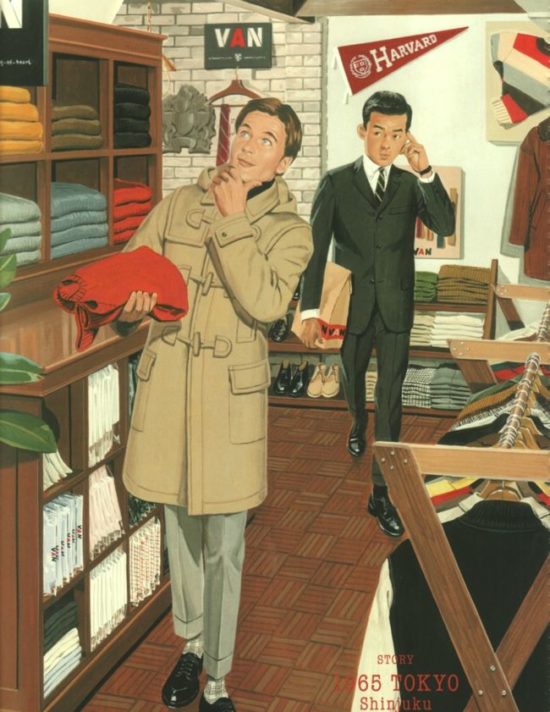

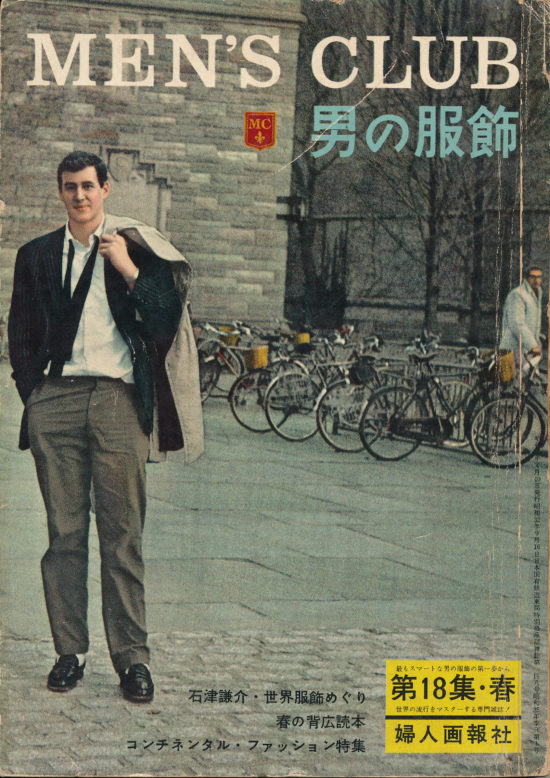

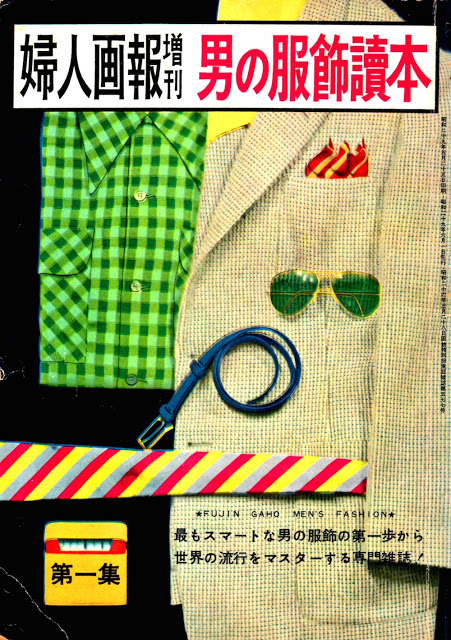

Ametora means “American traditional†and started in the ’80s in Japan. It refers to collegiate American East Coast or what we usually call Preppy. “Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style” is also the title of a book by Tokyo-based W. David Marx that delves into the cultural history of Japanese menswear.

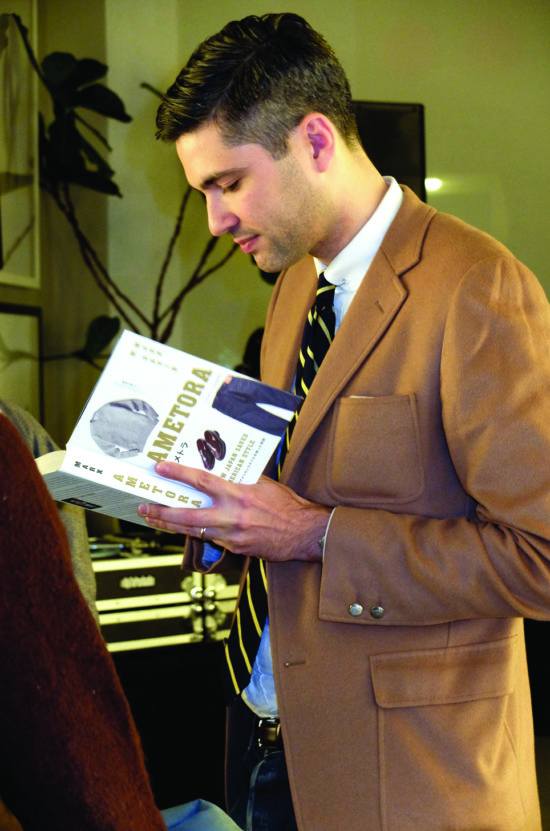

David will be at our shop, Pawnstar, tomorrow (Saturday 4/22) at 5:00pm to sign copies of his book and talk about Japanese dandy style and how it preserved and shaped American preppy.

The address of Pawnstar is Room 104, Bldg. 1, The Clement Apartments 1363 Fuxing Zhong Lu,Xuhui district å¾æ±‡åŒºå¤å…´ä¸è·¯1363弄克莱门公寓1å·æ¥¼104室

Here are reviews from GQ and Japan Times and get a copy on Amazon! Click more for additional pics.

Below is excerpt from his book

Here’s the unedited, long part of my book that takes place in Tianjin:

Ishizu’s playboy life in Okayama would have gone on unabated if not for the lurch towards military dictatorship in the 1930s. After Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, the government worked to stamp out all varieties of dissent and heterodoxy. Fanatical right-wing “patriot†groups assassinated democratic politicians and attempted coup d’états against a government they saw as insufficiently loyal to the Emperor. Things hit very close to home for the Ishizus in 1932: the older sister’s brother-in-law, Professor Yukitoki Takigawa, lost his job at Kyoto University merely for voicing the liberal idea that judges should work to understand criminals’ reasons for committing crimes. The Imperial government heavily regulated industries to control war supplies, and in 1938, Kami Ishizu was forced to cap its business activity. TadazŠand Kensuke could only open the store for three days a week.

A darkness descended upon Japanese society, but things looked sunnier in the Asian colonies. In the early 1930s, the Japanese Empire controlled Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, as well as swaths of Eastern China. In mid-1939, Kensuke’s hometown friend Teruo ÅŒkawa received a letter from his older brother in the booming Chinese port city of Tianjin asking to come and help with his successful department store ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ. The elder ÅŒkawa also invited Kensuke to come to Tianjin. This was great timingl for Teruo, who had just been kicked out of the house for punching out an annoying but critically important customer of his father’s.

Kensuke felt a responsibility to look after Kami Ishizu in Okayama, but with business grinding to a halt under government regulations, his father told him to go off and try something else. Ishizu was thrilled to leave. He reminisced later in life, “The young men of that era grew up with freedom. I, in particular, needed new forms of stimulation on a daily basis and longed more and more to be over in the free-wheeling Tianjin.†There was also a more urgent motive to leave town: Kensuke heard whispers that his favorite geisha was pregnant. The rumors ended up being false, but Ishizu did not want to stick around to find out. He accepted the elder Ōkawa’s offer, and in August 1939, Kensuke and Masako boarded a boat with their three children for a five-day voyage to Tianjin.

In the early 20th century, Tianjin was famous for its international flavor. The major powers divided the city up into self-governed concessions, each incorporating the unique architectural styles of the home country. The Japanese took full control of Tianjin in 1937 but allowed the remaining British, French, Italian concessions to operate independently until 1941. Beyond the Chinese population, the city hosted a diverse group of Europeans — from British country-club elites in tails to disheveled White Russian émigrés. The Ishizus joined a population of 50,000 other Japanese, enough to support two Japanese-language elementary schools and retailers like ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ that imported goods directly from the home islands.

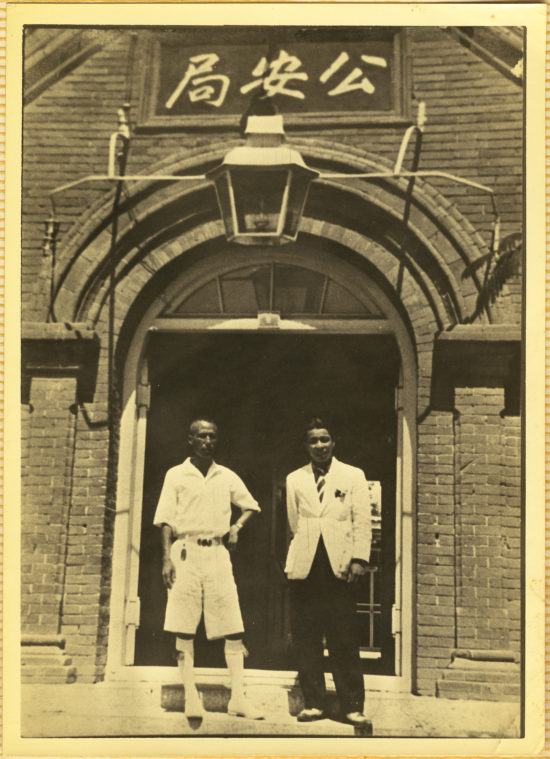

At the age of 28, Ishizu began a new life in China as sales director of ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ. As a retailer of men’s clothing and other high-end goods, Ishizu could finally wear the dapper suits he so loved. With most department stores facing crushing regulations back in Japan, ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ became the highest grossing retailer in the entire Empire. Ishizu was a natural salesman and delighted in dreaming up new promotions for the store. He eventually also took over clothing production. When the war got in the way of distribution routes from the home islands in 1941, Ishizu brought over his tailor from Okayama and started manufacturing suits in China.

In Tianjin, Ishizu fulfilled his lifelong dream of living like a Westerner. He was incredibly rich by Japanese standards. Beyond the store turning an amazing business, he made the modern equivalent of $50,000 in one night at a Shanghai casino. The family resided in a British-style home with a Chinese housekeeper. They ate oatmeal and toast for breakfast. The children dressed in adorable suits. Ishizu traveled to work in the back of a rickshaw like a British colonial official. He also swore off Japanese-style squat toilets for the rest of his life.

Ishizu did not stick with other Japanese but integrated with the wider international community. He picked up basic English and Russian and learned Chinese from a local geisha. He frequented British tailors to learn trade secrets, heard the latest about the war at the local Jewish club, and bet on Jai Alai in the Italian concession. As the war between Japan and China intensified, Chinese girls cooled to the Japanese occupiers, so Ishizu set his sights on Russian ingénues instead.

Tianjin gave Ishizu not just a better life than he had in Japan but an excuse to avoid hard times back at home. As the imperialist expansion in China extended into a full scale conflict with the United States from December 1941, Japan mobilized the home front for total war. While Ishizu lived like a young European prince, his home country systematically rolled back all Western influences from local culture. New regulations demanded that companies take English words out of brand names and advised against writing words horizontally in the Western style. Baseball avoided extinction by replacing its foreign-derived terminology with native Japanese words for strikes and home runs. While Ishizu wore his high-end three-piece suits, Japanese men back in Okayama wore mandatory khaki-colored uniforms called kokuminfuku (citizen clothing).

The Japanese suffered through austerity, but from April 1942, they also faced physical harm with the start of American bombing campaigns.Thanks to a part-time job as a military glider instructor, Ishizu avoided the terrible realities of the front lines. Tianjin itself saw little conflict. Ishizu’s eldest son ShÅsuke remembers, “No part of Japan’s wartime experience came to Tianjin. At most we would have air-raid warnings when B-25s would fly overhead. But they were just passing over and had no reason to bomb Tianjin. I loved to go outside and watch them fly over.†While the Japanese public heard daily propaganda about “devilish Anglo-Americans,†Ishizu fraternized with the enemy and imitated the devils’ lifestyle.

By 1943, Japan’s prospects for victory looked bleak. As Allies slowly chipped away at the Japanese Empire, the ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ team came to worry that their trade in luxury goods looked like an unpatriotic enterprise. They also assumed the Army would soon commandeer the store and ship everyone off to the front lines. The elder ÅŒkawa brother decided to sell off ÅŒkawa YÅkÅ to rival chain Kanebo and split the money between the employees. With piles of cash in Tianjin likely to be confiscated on return to Japan, Ishizu chose to remain in China.

Now committed to the Japanese military cause, Ishizu and the ÅŒkawa brothers shaved their heads and enlisted. Ishizu took a cushy position as a naval attaché. He refused to wear the standard-issue cotton fatigues, instead ordering a dashing version of the uniform in high-quality British serge wool. The military tasked Ishizu with running a factory that made glycerin for use in dynamite. Broken distribution lines, however, meant that none of the glycerin made it to the front lines. Instead of letting the materials go to waste, Ishizu retooled the factory to make clear soaps scented with Parisian spices. They became a hit with the local Chinese and money again piled up. He later felt remorse about this dereliction of duties. “I was ashamed that I never did any work of use to my country. We probably lost the war because of Japanese like me.â€

From this makeshift soap factory in August 1945, Ishizu heard Emperor Hirohito’s radio broadcast announcing the Japanese surrender to Allied Forces. The city experienced neither military battle nor Chinese Communist guerilla attacks, but suddenly, the city was no longer Japanese. The Chinese would take back control of Tianjin. This disconnection to the war’s horrors cast an eerie pallor over the city in the early days of defeat.

The Nationalist Chinese forces ultimately prevented mass violence against the Japanese occupiers, but they treated Ishizu with complete contempt. They constantly interrogated him at the factory, looking to pilfer barrels of glycerin. Ishizu spent most of September 1945 locked in a former Japanese naval library and in constant arguments with the Chinese military.

Things improved, however, with the arrival of the U.S. 1st Marine Division in October. The Marines came ashore to an impromptu victory parade, with thousands of Chinese and European expatriates storming the streets to greet their liberators. The Americans then liberated Ishizu. Looking for Japanese who could speak English, a young Lieutenant O’Brien broke Ishizu out of the library with two pistols pointed to the sky. The Americans then used him as an ambassador to the Japanese population.

In the subsequent weeks, Ishizu struck up a friendship with O’Brien. The American regaled Ishizu with stories of his undergraduate life at Princeton — the first time Ishizu heard about the “Ivy League.†Although their friendship was short lived and Ishizu never even learned O’Brien’s first name, Ishizu would always harbor pleasant feelings about American collegiate life.

Through luck and cunning, the 34 year-old Ishizu avoided the worst of Japan’s repressive fascist society and wartime violence. And even after his country’s humiliating defeat, he parlayed his cooperation with the American forces into material comfort. As the Japanese awaited repatriation from Tianjin, Ishizu’s family spent their days playing volleyball and visiting with Americans at their homes. Ishizu gamed the rationing system, eating sukiyaki and other gourmet meals each night.

Ishizu did not taste the War’s bitterness until March 15, 1946, when the Americans put him and his family on a cargo ship back to Japan. He left behind everything that could not fit in a backpack, including the modern equivalent of $20 million in cash. They spent a week with hundreds of others on the rickety boat with shallow cots for beds and two primitive toilets. Everyone received a single meal per day. Sadly, the harsh life aboard the American cargo ship would was not just a temporary hardship for Kensuke Ishizu and his family — these conditions reflected the new reality for the people of Japan.

[…] The Ametora event with David Marx that we mentioned before has now been rescheduled and will now be occurring on May 21 at Pawnstar on 1363 Fuxing Middle Road. […]

[…] AMETORA: DAVID MARX AT PAWNSTAR The Man Who Brought Ivy To […]